25 Mar 2013

8 mins readLock Lock Lock: Enter!

Java locks

There are 2 majors locks in java:

- synchronized keyword

- java.util.concurrent.Lock (with ReentrantLock implementation).

In this post we will dig into internals of those locks.

Synchronized keyword

The main advantage of this lock mechanism is the language integration. With this, JVM can optimize freely without impacting existing code.

Also every object carries structure allowing to perform locking anywhere. However this comes at a cost of larger objects.

Each object has at least 2 words (2x4 Bytes for 32 bits & 2x8 Bytes for 64 bits, excluding CompressedOops). First word is known as Mark Word. This is the header of the object and it contains different information, including locking ones. Second word is a pointer to metadata class defining the type of this object. This includes also the VMT (Virtual Method Table, cf Virtual Call 911).

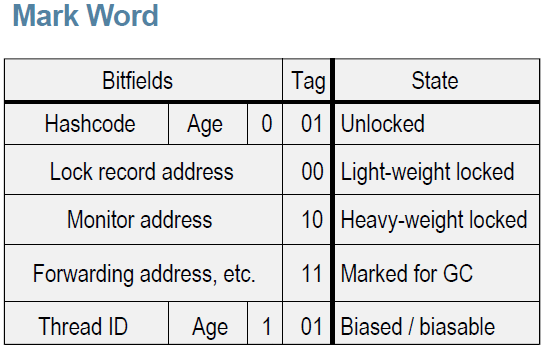

The Mark Word can be summarized by this table [1]:

The Mark Word encodes different informations depending on the state of the object indicated by the 2 lowest bits: the Tag. If the object is not used as a lock, the Mark Word contains cached version of the hashcode and the age of the object (for GC/survivors). Then, there is 3 other states for locking: light-weight, heavy-weight & biased.

Light-weight

If we try to acquire an uncontended lock, there is a light-weight mechanism involved: a CAS (Compare-And-Swap) operation is performed to displaced the Mark Word to the current stack. Since synchronized can only be used into one and same stack, it stores previous value of Mark Word into the stack and allows to store more information to handle contended & recursive cases.

What is generated by the JIT for the following code?

{

synchronized (obj)

{

i++;

}

}

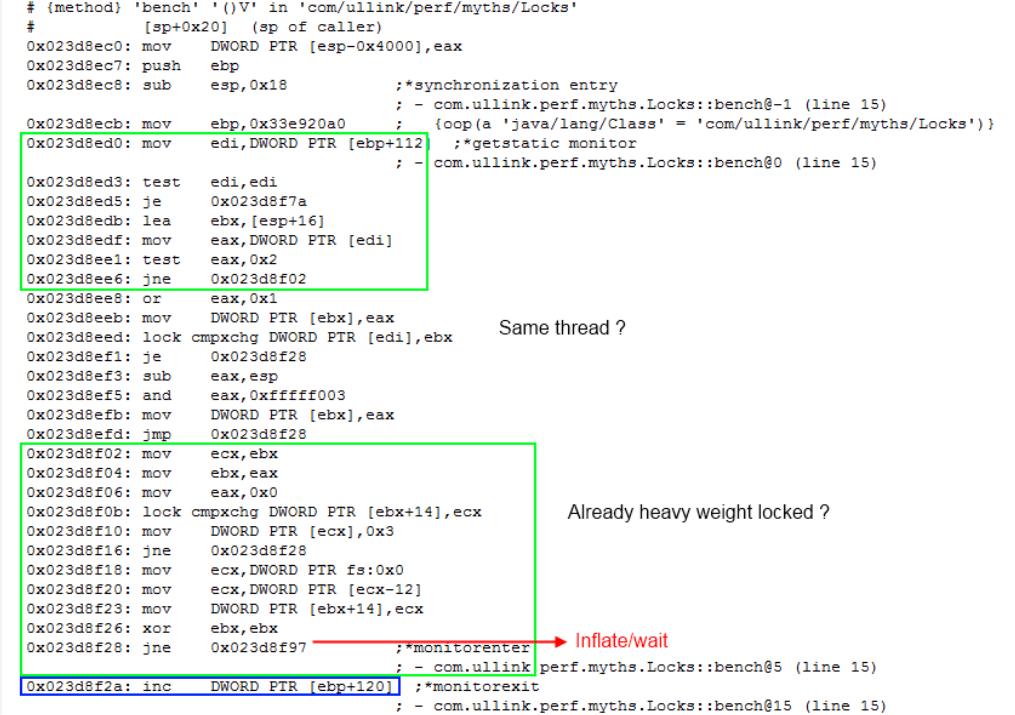

I have highlight in green above what is executed in uncontended case, in best case. In blue the code inside the synchronized block.

Basically, the critical part is the CAS operation: lock cmpxchg

In contended case, the lock is inflated to heavy-weight mechanism.

Heavy-weight

If the lock detects contention with another thread, the lock is inflated. It means that a special object “monitor” is allocated to store lock information with also Mark Word information since then, Mark Word contains address of this monitor. Monitor object stores WaitSet for threads waiting to acquire the lock. Lock mechanism is based on OS primitives like Mutex or Events. This implies a context switch for the Thread. This is why this heavy-weight should be avoid for performance.

Biased

If the lock is only aquired by one thread, JVM can optimize it by biasing the lock toward this thread. It means that we keep into the MarkWord the thread Id which acquires the lock and then subsequent lock acquisition is just a simple check that this the same thread id, and without any CAS instruction.

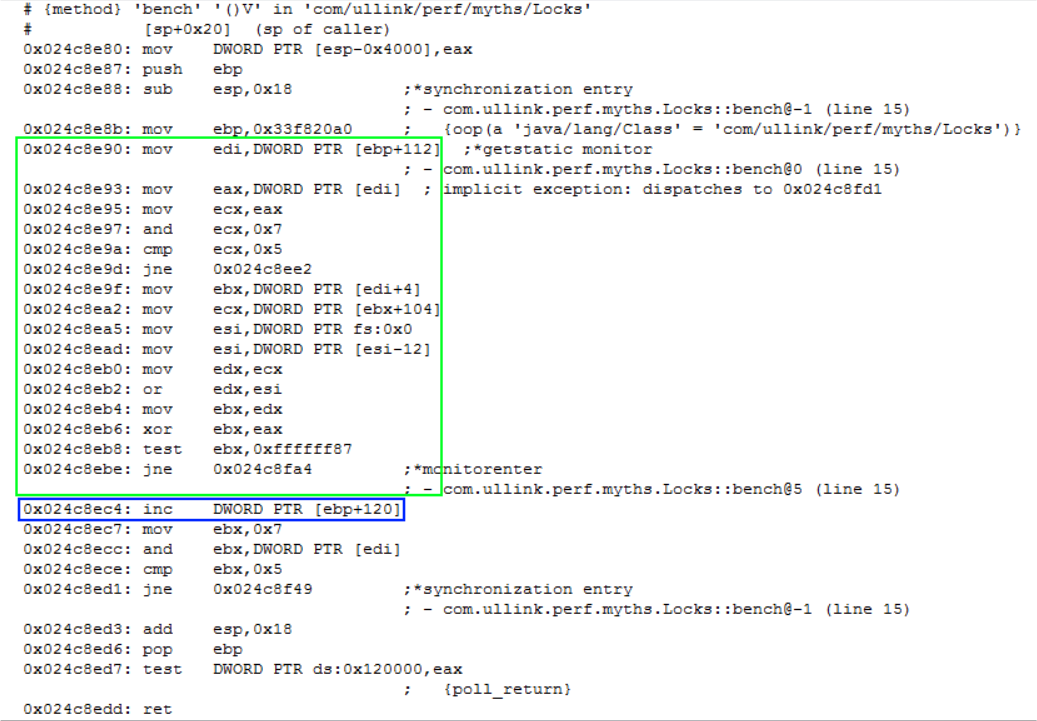

As you can see, the instructions highlighted in green are basic, no lock cmpxchg.

So it seems better, but in fact it comes with a high cost: If another thread try to acquire this lock, JVM need to revoke the bias. And bias revocation costs a safepoint. It means that all threads must be stopped in order to perform the revocation.

So in certain circumstances, it is better to deactivate this kind of optimization: -XX:-UseBiasedLocking

Please note also that BiasedLocking is enabled only 4 seconds after startup. You can tune it by -XX:BiasedLockingStartupDelay=4000

Other optimizations

In some cases, JVM can apply additional optimisation. Mostly for full synchronized object like StringBuffer or Hashtable. For those objects, since we can call multiple times synchronized methods, we can avoid lots of locking/unlocking by grouping method calls under a same large lock.

{

sb.append("foo");

sb.append(v1);

sb.append("bar");

}

Here the 3 calls are under a unique and large lock to avoid 3 locking/unlocking operations. This is the lock coarsening.

Then, if we apply Escape Analysis and we detect that StringBuffer instance does not escape from a local scope, we can prove that those synchronized methods will never be contended.

{

StringBuffer sb = new StringBuffer();

sb.append("foo");

sb.append(v1);

sb.append("bar");

return sb.toString();

}

In this case sb instance is local and there will be never contention in here. So we can suppress locks. This is Lock Elision. However, those optimizations seems to be very specific for this kind of object, and are not very common in today’s code.

ReentrantLock

Unlike synchronized, ReentrantLock is a regular class integrated into the JDK. But some primitives are provided by the JVM like the ability to perform CAS operations through Unsafe.compareAndSwapInt() method. This method is handled specifically by the JVM because it is declared as intrinsic. It means that JIT can generate special set of instructions for it instead of the regular call to JNI implementation.

Intrinsics

If we take a simple example with AtomicInteger class, compareAndSet method is implemented like this:

public final boolean compareAndSet(int expect, int update) {

return unsafe.compareAndSwapInt(this, valueOffset, expect, update);

}

And compareAndSwapInt is decalred in Unsafe Class like this (extracted from OpenJDK sources):

public final native boolean compareAndSwapInt(Object o, long offset,

int expected,

int x);

So it is declared as a JNI implementation that I have also extracted from Open JDK sources:

UNSAFE_ENTRY(jboolean, Unsafe_CompareAndSwapInt(JNIEnv *env, jobject unsafe, jobject obj, jlong offset, jint e, jint x))

UnsafeWrapper("Unsafe_CompareAndSwapInt");

oop p = JNIHandles::resolve(obj);

jint* addr = (jint *) index_oop_from_field_offset_long(p, offset);

return (jint)(Atomic::cmpxchg(x, addr, e)) == e;

UNSAFE_END

Normally, a call to method like this, is a regular runtime call to the compiled code above. Let’s verify on disassembly version of the follwoing Java code:

static AtomicInteger i = new AtomicInteger(42);

static void call()

{

i.compareAndSet(42, 43);

}

0x02538c8e: mov ebx,0x150

0x02538c93: mov ecx,DWORD PTR [ebx+0x569cef0]

;*getstatic i

; - com.bempel.sandbox.TestJIT::call@0 (line 31)

; {oop('com/bempel/sandbox/TestJIT')}

0x02538c99: test ecx,ecx

0x02538c9b: je 0x02538cc5

0x02538c9d: lea ebx,[ecx+0x8]

0x02538ca0: mov eax,0x2a

0x02538ca5: mov ecx,0x2b

0x02538caa: lock cmpxchg DWORD PTR [ebx],ecx

0x02538cae: mov ebx,0x0

0x02538cb3: jne 0x02538cba

0x02538cb5: mov ebx,0x1 ;*invokevirtual compareAndSwapInt

; - java.util.concurrent.atomic.AtomicInteger::compareAndSet@9 (line 107)

; - com.bempel.sandbox.TestJIT::call@7 (line 31)

As you can see, the code contains in fact very few instructions, and the main one: lock cmpxchg

Uncontended case

For the following code:

{

lock.lock();

try

{

i++;

}

finally

{

lock.unlock();

}

}

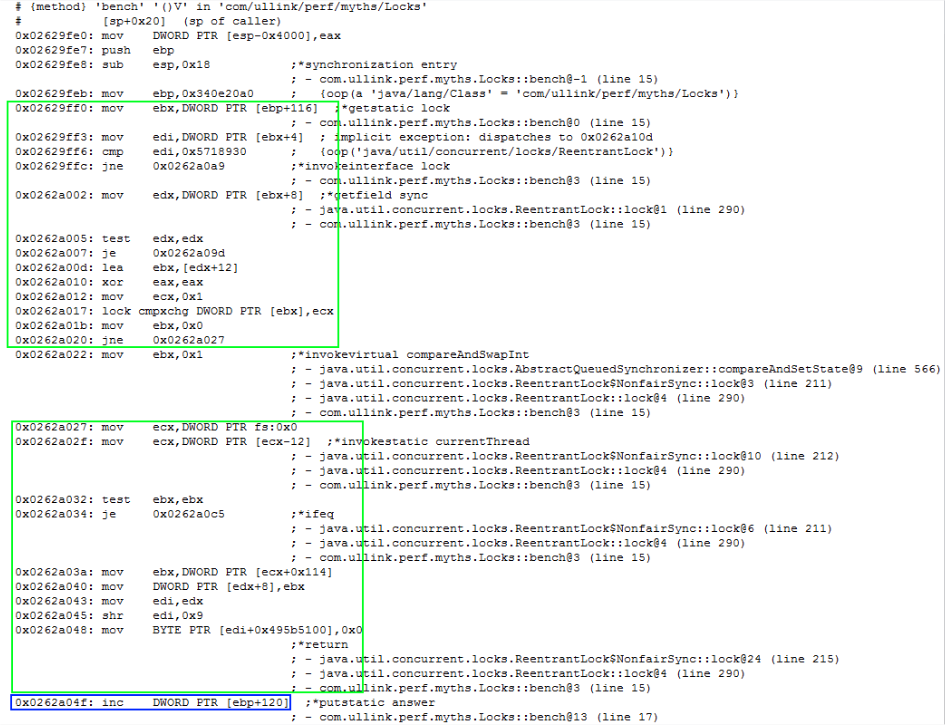

We have the following output for disassembly:

Highlighted in green, the path executed when we acquired successfully the lock. Notice again the main instruction lock cmpxchg.

Conclusion

Except for biased version, other versions are similar. So here no clear winner for what is the fastest lock.

Biased locking seems very efficient here, but at a high cost of a safepoint if revoked.

ReentrantLock is more stable in terms of execution since there is no special optimization beside the intrinsic form of CompareAndSwap operation.

In any case you can notice that there is overhead by using lock, even in best case when there is no contention.

[1] From presentation: The Hotspot Virtual Machine by Paul Hohensee